Too Much Minimum, Too Little Viable

Your unfinished zombie products will come to haunt you one day

Your unfinished zombie products will come to haunt you one day

Let me tell you the story of Paul. Paul is known in his company as a person who has a bias for action. Who delivers business results in short amounts of time. For this reason, he’s trusted with strategic projects, frequently changing context. Paul is ruthless in the quarterly plannings. He sets aggressive business goals and is very assertive with the team on why they should be. He’s the first to suggest “MVPs” for the team and always finds inventive ways to use spreadsheets, manual and semi-manual processes to drive value. After all, we must learn fast and to do that. We gotta do things that don’t scale. His teams frequently hit their OKRs. He’s great at sharing those results and the creative ways they managed to do something that should take 3 months in 3 weeks and iterate on it. He shines the spotlight on the team–and himself, of course–and gets rewarded for it. He’s known as a problem-solver. He gets things done. So he goes on to the next project and does it again, stays for 3-4 months tops on each product.

What the spotlight doesn’t catch so well is what’s left behind. The debt. The unfinished products. The unfinished learnings. The amount of load the teams that are left behind will have to carry. The company’s expectations that the team will continue to reach outsized results with undersized effort and the lack of time. The culture of short-sightedness. The team that is left behind has two paths:

- Define a strategy to deal with the debt, request for time to productize and optimize the previous solutions, reduce expected business results or the worst one:

- Continue setting high expectations and finding creative ways to build things that don’t scale. Jam them together and see if poop + poop = diamond.

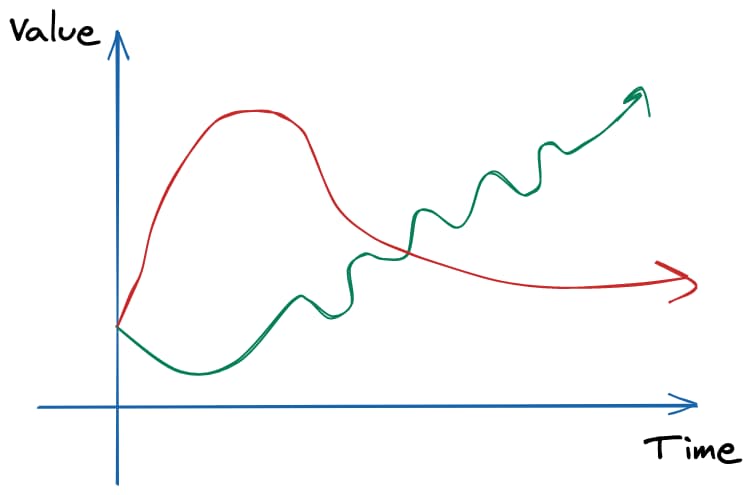

Teams that go with one are taking a professional risk. It’s not rare to see people consider too soon that “we’ve reached the point of diminishing returns with this,” discontinue the team and look back at the work as a failure–increasing the problem altogether. But they’re doing the right thing.

It’s hard to quantify and shed light on how much these issues matter. There’s a huge barrier, and things were not done like this in the past when the team was thriving. So Paul’s last team–the shipping team–decides to go with the second path and do more MVPs.

The alchemy some people believe that Agile means

The alchemy some people believe that Agile means

By this time, Paul is already in a different team, focused on a new project. On the shipping team, debt is piling up like crazy. The team needs to constantly deal with issues that happen and hinders the performance of the Operations team. Trust starts to erode between the teams. Fixing and building new features start taking longer and longer. The Operations team believes the Product team is slow and doesn’t care about the customer. The Product team starts to think that the operations team doesn’t understand anything about the problem. Shipping starts to fail, and the problem grows each day. Months go by; people leave the teams, results are not improving.

The company sees this and places Paul back into Shipping. He has a bias for action. He’s going to fix this. He’s ruthless in understanding the problem, talking to the teams, talking to everyone. He gets to the bottom of the problem. The team is fed up with the spaghetti the product has become and has had it with it. So the solution is clear: We need to rewrite the software. And we know how to do that fast, right? Just do an MVP 😬 In 3 months, we can rebuild this to that new technology, and it’s going to fix everything. You see where this is going. The cycle restarts, only this time with more things to build and more issues to solve.

Paul is not necessarily a person. Paul can be a culture. The early days of the company are very intense, and the practices we develop in those early days can stay within the company’s processes, teams, people–they can become part of the culture. To a point where if we don’t do them, even if it’s the right thing, we feel wrong and might even be penalized for it. Context switching all the time, overemphasizing short-term goals soon makes us forget that MVPs are learning tools, and they become the default mode for building software.

So, which one would you rather be?

MVPs are not crutches to forget about Quality. They are not incomplete products, untested products, and they are not a crappy version of what you want to build. When we incur debt to build them, either by inefficient back-office processes or technical issues we’re going to face in the future, that debt will grow if the company grows. We need to keep it in check. We need to have a plan for it. But, most importantly, we need teams to have support in defending paying that debt. We need teams to say that they will focus on Quality at all stages of Product development and be supported in it.

Being agile and putting software in the customers’ hands does not mean pilling a bunch 💩 together and expecting it to become a diamond 💎. It means incrementally working to make the Product better while maintaining the expected quality. With each day that goes by, our users expect more quality from us. That bar is always rising. So let’s keep ourselves above it 😉