The Feedback You Receive Is Horrible. We're Going to Fix it.

The importance of learning from failure is part of conventional wisdom now. As a result, we encourage people and Organizations to fail fast, to fail cheaply. We encourage managers to display Radical Candor and give harsh feedback, showing people their shortcomings but doing so with love. But there's something fundamentally keeping people from learning from that feedback and their failures. That's clear when we look at the data.

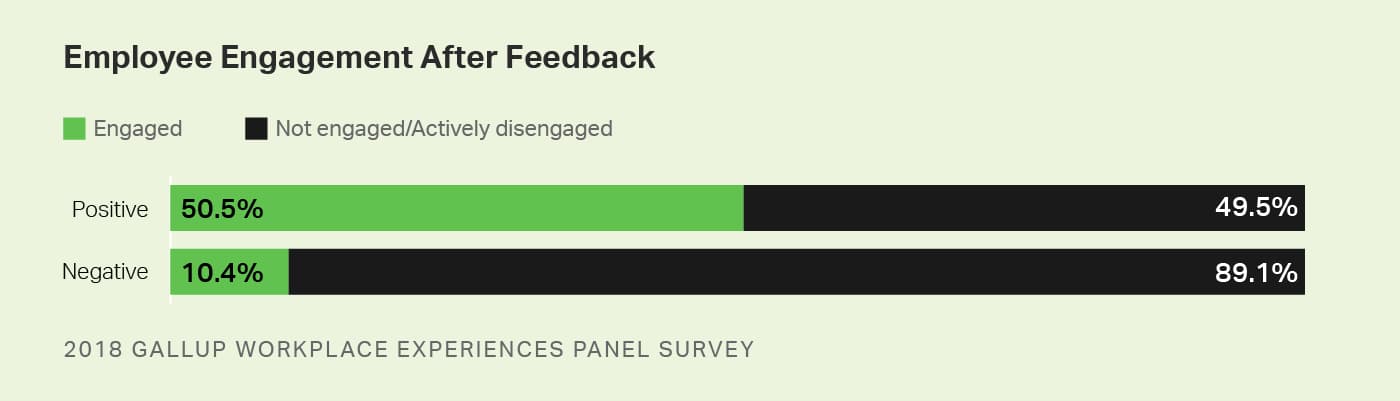

Graphics from Gallup's Why Employees are Fed up with feedback

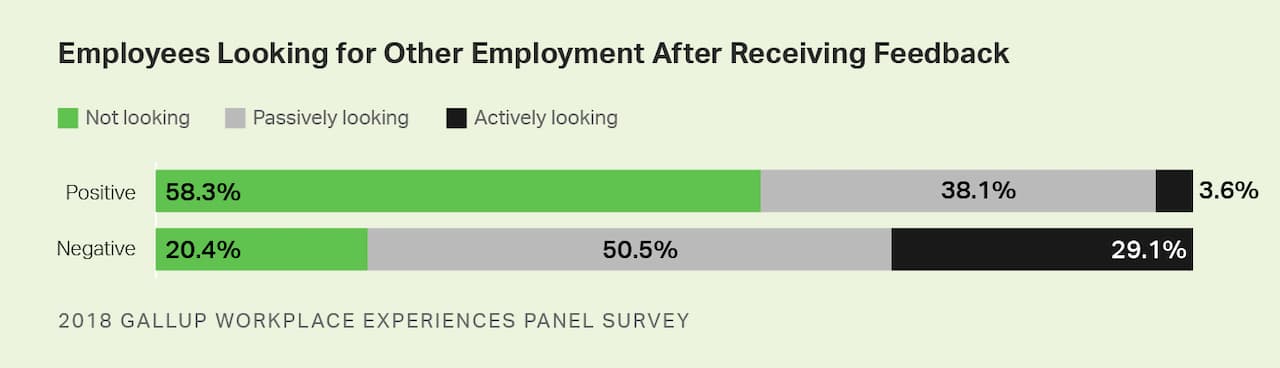

Graphics from Gallup's Why Employees are Fed up with feedback

Research also specifically shows that we have a tough time learning from our failures. This excerpt by Shane Snow from his fantastic book, Smartcuts, explains this very well:

"In the late '90s, researchers figured out a way to do coronary artery bypass grafting, (CABG) without stopping the heart. This meant surgeons who'd been performing the surgery for decades had to learn a new procedure, which required more dexterity. With it, more lives would be saved, and side effects spared.

This change excited Bradley Staats, who was then a researcher at Harvard Business School. Not because he was expecting heart surgery anytime soon, but because he was conducting research on failure, and suddenly a whole lot of surgeons were about to fail, despite a life-or-death motivation not to.

For ten years, Staats and his associates followed surgeons as they learned to do CABG on beating hearts. Staats observed a total of 6,516 operations and tracked the mortality rates of patients from surgeon to surgeon—adjusted for factors like age and health. He studied how the surgeons learned to get the procedure right, and what happened when they didn't. By the time the researchers published their results, Staats had become a professor at UNC and a slew of patients had lived to eat more cheeseburgers.

But along the way, a number of surgeries by the transitioning doctors ended in failure. Staats and his colleagues combed through the data from all the surgeries, looking for patterns: How did a surgeon's failure in one operation affect future surgeries? How quickly did doctors learn, and did failure help them improve?

They called the results a 'paradox of failure.'

It turns out that the surgeons who botched the new procedure tended to do worse in subsequent surgeries. Rather than learning from their mistakes, their success rates continuously declined. On the other hand, when surgeons did well on the new surgery, more successes tended to follow.

But what's really interesting is what happened to the surgeons who saw their colleagues fail at the new CABG procedure. These showed significant increases in their own success rates with every failure that they saw another doctor experience. Further perplexing, however: seeing a colleague perform a successful surgery didn't seem to translate to one's own future success.

It was indeed a paradox. Screwups got worse. When colleagues screwed up, observers got better. When a doctor succeeded, she did better on her subsequent surgeries. When her colleagues did well, it didn't affect her.

There's no fun in the funeral of a heart patient whose surgery you failed. But every doctor fails sometimes. Seasoned physicians learn to become mentally and emotionally immune to it. They learn to live with the reality that some patients don't survive. Staats concluded that this coping mechanism was itself responsible for the paradox. He and his colleagues called this attribution theory. The theory says that people explain their successes and failures "by attributing them to factors that will allow them to feel as good as possible about themselves." [...] "When interpreting their own failures," Staats explains, "individuals tend to make external attributions, pointing to factors that are outside of their direct control, such as luck. As a result, their motivation to exert effort on the same task in the future is reduced." Interesting. When doctors failed due to what they perceived as bad luck, they didn't tend to work any smarter the next time. They attributed failure in a way that made them feel as good as they could about themselves. "Even though an individual failure experience may contain valuable knowledge," Staats says, "without subsequent effort to reflect upon that experience, the potential learning will remain untapped. "Further, since individuals tend to seek knowledge about themselves in ways designed to yield flattering results, even if someone were to engage in reflection after failing, he might seek knowledge to explain away the failure." [...] However, when failure isn't personal, we often do the opposite. When someone else fails, we blame their lack of effort or ability. When we see people succeed, we tend to attribute it to situational forces beyond their control, namely luck." (Emphasis mine).

When we look at all this research, it's easy to assume that negative feedback is inherently flawed and positive feedback is effective. But no matter how engaged people feel, they still need to improve and learn from their failures and successes. The problem here is not on the feedback itself. It's in how it's delivered and how it's received.

Using Feedback to Fuel your Growth

We can't control how others deliver feedback to us, but we can improve how we react. The challenging part about negative feedback is turning off our egos and being confident enough to extract what's helpful from what we're listening to. It's tough but, when we do, feedback becomes a powerful thing. When we separate our ego from the discussion, we can start to see feedback as a gift.

As a manager, I've seen feedback to me dry out. My work is inherently behavior-driven. It's harder to give me feedback on specific tasks because I work primarily through others and people have a hard time giving feedback on behaviors and things that aren't tangible. And working without feedback was pushing me down. I was taking too long to learn from my mistakes. So I had to hone my feedback receiving skills to make it more frequent and make the most of the ones I receive. Here are some of the things that help me make the most of it:

Make it specific

When someone says to you, "Good Job," your first instinct should be to ask: "What part?" or "What specifically about that did you like?" and "What seemed to work well?" or "How did that help you?". The point here is to debug excellence. Understand what that person perceives as something good. When receiving negative feedback, we need to act the same: "Could you give me an example of a situation?" or "What other project/time we worked in the past together did I have a better performance on so I can mimic that?" and "How did this impact you?" If the information isn't inside the feedback, we can make it more actionable by dissecting it.

Make it frequent

Always ask for feedback right after something you deliver, even if you're sure it was excellent. Be specific on what you want feedback on, invite a challenge to what you did and keep the questions open-ended. An example: "What's one thing you would have done differently?" or "What is the least clear part of the plan to you?" I wrote more on how to invite more feedback in the last article.

Don't ask for feedback only from your manager. Get feedback from your peers. Ask for feedback from experts in your field. If you're a leader, the people you lead are one of the best sources of feedback you'll ever have.

Make it impersonal

Depersonalize the feedback you receive. Keep your ego out. Assume everyone is coming from a place of trust and respect for your work. Even when they aren't, putting some space between your work and who you are as a person will help you see it clearly and absorb what's valid from the feedback. Rely on your past achievements to see your value and don't question it. Paradoxically, when we're questioning our value, we aren't more prone to learn from our mistakes. It's the other way around. We start trying to prove ourselves and attribute our mistakes to circumstances, losing opportunities to grow.

Getting feedback from people who 1. are experts on the work that we do or 2. are directly impacted by the work we do is a great way to learn and grow faster. No amount of failure will make us better without reflection. And it's not always easy to pinpoint what made us succeed in different scenarios. So we need all the help we can get. Feedback is a gift, so it's also our job to make the most of it.