It's a Sea Chart, not a Road Map

What should I work on next? The answer is usually in our carefully built and planned out Road Map. There we have a safe, prioritized, and estimated set of tasks. It makes our decisions easier.

Roadmaps appeal to us. They allow us to:

- Make sure we're always working on the highest priority items.

- Communicate clearly with stakeholders in what order and how long we'll take to do each part of our projects

- Make it very easy to document and sync decisions that we made in the past

There is one colossal con, though: It tells people what to do, not what to accomplish. It commits us to activities, not to outcomes.

Roadmaps give us a sense of linearity. They provide us with efficiency, which can be very powerful. But can also drive us to commit to the wrong things. We want everyone in our teams to be focused on outcomes, to own the business goals we're responsible for. So what can we do to fix that?

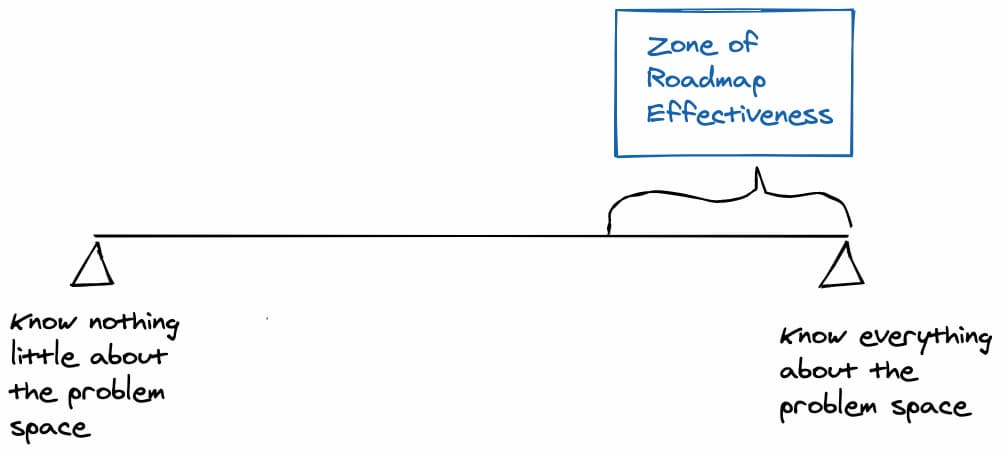

Roadmaps are more effective when we know a lot about the problem space

Roadmaps are more effective when we know a lot about the problem space

Turning your Roadmap into a Sea Chart

When we're going on a road trip, we have a destination in mind, and it's reasonably predictable which road we'll take to get there. Someone studied the path and built the infrastructure that enables us to have that predictability. Armed with a map, we can quickly determine all milestones we want for our road trip before arriving at our destination, and we can expect that we'll reach them on time.

When we're sailing, we don't have such luxury. We know the destination, but the infrastructure is not there, and conditions frequently change without notice. We need to understand the sea, the currents, the wind. Even experienced sailors have a hard time predicting how long they'll take to finish a long trip accurately. Not everything is out of our control. We can recruit an experienced crew and use a sturdy boat. We can learn from people who have sailed the same sea and made the same trip in similar conditions. All this makes us more prepared and is critical, but we'll still have to adjust to whatever happens along the way, and a lot will happen.

Building Products is often like sailing. Even if we do a lot of research, we still know very little about the problem space. Even if we have a clear north star, short-term priorities change like the wind. We need to adjust. Learning fast about those conditions allows us to move more quickly. In these scenarios, thinking about our plans as Sea Charts is more useful than Road Maps. I've found that some things help us in that:

- Focus on the North Star

- Break the travel down into several short trips. Use each short trip to make the next one faster and safer

- Committing to details only when we're sure about them

Focus on the North Star

The outcomes are what matter the most to us–context matters more than content. We need to gather enough information to provide us with insights into which outcomes we need to pursue. Gathering information doesn't mean only analyzing data. It means doing exploratory discoveries, and it usually means building experiments to learn new things and validate any knowledge we think we have.

I've worked on teams where the Designers and Product people are responsible for doing this work and reaching the North Star–the rest of the crew being involved only in estimation and execution. I urge you not to do that. It seems more efficient, but it's way less effective. No matter how well we communicate the goal, the rest will be less committed to it if they weren't a part of the process. Furthermore, even more importantly, we'll miss critical ideas, insights, and information.

Break the travel down into several short trips. Use each to make the next one faster and safer

It's easier to reason about short trips than it is about long ones. With the popularization of Agile, this should seem obvious by now. But frequently, we fail to use each shorter trip to review our strategy. We draw our roadmap several cycles ahead and commit to it instead. We forget that moving faster (with safety, of course 👀) toward the goal is more important than traveling the road we believe is the best one.

When we reduce the cycle time, we're trying to reduce the problem space to be efficient and effective inside it. Reducing the problem space in itself is very useful. But we can focus our efforts on learning about the larger context of the problem as well. At the very least, we need to be prepared to dramatically adjust our plans at each junction if we've found new information. And this is a good thing. Learning is what makes small product teams faster. Commit to learning. Be pissed when you haven't learned anything new about your user in the last month, not when you have to change your plan or leave work unfinished. The plan is nothing. Learning is everything.

There's no rule about how small your planning process should be. But I know that a good rule of thumb is handy, so start at six weeks, but stay vigilant and review if it matches your team/context

Committing to details only when we're sure about them

"Once we have made a choice or taken a stand, we will encounter personal and internal pressures to behave consistently with that commitment." Says Dr. Robert B. Cialdini in Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. "Those pressures will cause us to respond in ways that justify our earlier decision."

Committing and not following through is painful. That's how our brain works. It can also erode the trust people have in us. So we should always be very sure of how much we understand a problem, a goal, and our teams before making High Integrity Commitments.

"So the way we manage commitments is with a little bit of give and take." Marty Cagan helps us on how to do that in this article. "We ask the executives and our other stakeholders to give us a little time in product discovery to investigate the necessary solution, and validate that solution with customers to ensure it has the necessary value and usability, with engineers to ensure its feasibility, and with our stakeholders to ensure it is viable for our business (they can support this solution)."

We need to avoid commiting to a date, or even to a project when we haven't yet found a solution that we know a lot about and one that works for our business. Don't be afriad to say "I don't know yet if we can build that in this amount of time or even if that is the right thing we should build, but give me time and we'll figure it out together." Those who have all the answers probably haven't been asked enough questions yet.

Building Products is hard. We often commit to and focus on the wrong things. We need to embrace change. Adjust to what we can't control, and focus on what we can. By doing that, we'll not only get there faster but will also enjoy the ride. It makes us love the change because it brings us to places we never thought we would go.

Sailing can be a drag or it can be fun. You decide which, not the sea.

Sailing can be a drag or it can be fun. You decide which, not the sea.