Practice does not make perfect

My late grandma was tenacious, quick-tongued, incredibly bright, and a relentless woman–I loved her very much. She was also a bad cook. Every day for at least 80 years, she would wake up at 4:00 AM sharp and start cooking beans and other foods her family would eat throughout the day. She had 15 children, so that was a lot of cooking. I'd say there aren't many people that have had more practice in cooking than my Grandmother–she certainly got way more than 10.000 hours in. YYet the food was never great. I don't want to seem unimpressed–the consistency and dedication she had are beyond what I could do, and she cared a lot–but the food was just not great. To me, that's proof that we can go our whole lives doing things and never really get great at them.

Hands-on learning, learning by doing, has become very popular. Like everything that gets famous, we lose information when we communicate about it, and people will understand it very differently. I figure that's how the notion that if something is not immediately useful for what we need to accomplish, it's not worth studying. While that attitude might help early on, it slows careers down significantly after a certain point. Things get more challenging, more complex, interconnected, and less obvious. We miss out on opportunities and build the wrong things, getting only marginally better and not growing as fast as we used to.

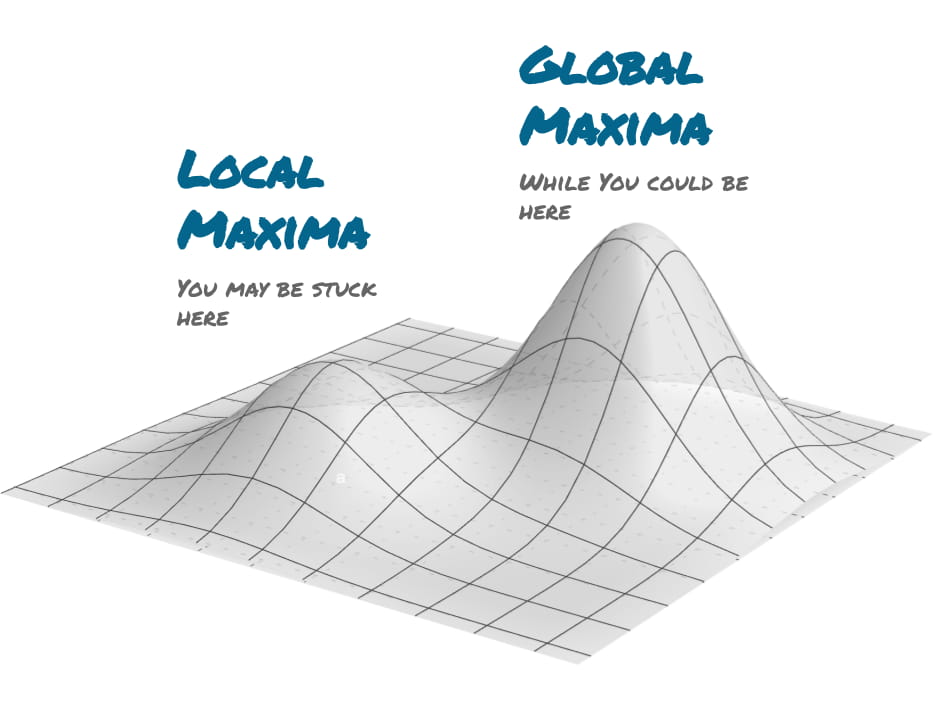

If we focus only on optimizing what's immediately in front of us, we can get trapped in local maxima. It may leave us for way too long on a single hill and not make us find ways to improve continually.

In truth, we probably will never reach the Global Maxima, but there's always a higher hill to go for next.

In truth, we probably will never reach the Global Maxima, but there's always a higher hill to go for next.

By developing some habits, we can overcome that chasm repeatedly in our careers. I'll focus on that–habits. Not on format or resources because we all learn differently, and I believe each of us is the best at finding what works.

Manage risk, but focus on long-term results

Knowledge is an investment. We pay with our time. We get information and experience back. So bear with me stretching some investing analogies here. The first one is from Pragmatic Programmer: Your Knowledge Portfolio. The basic idea is that managing a knowledge portfolio is very similar to managing a financial portfolio. From the book:

- Invest regularly. Just as in financial investing, you must invest in your knowledge portfolio regularly. Even if it's just a small amount, the habit itself is as important as the sum. A few sample goals are listed in the next section.

- Diversify. The more different things you know, the more valuable you are. As a baseline, you need to know the ins and outs of the particular technology you are working with currently. But don't stop there. The face of computing changes rapidly—hot technology today may well be close to useless (or at least not in demand) tomorrow. The more technologies you are comfortable with, the better you will be able to adjust to change.

- Manage risk. Technology exists along a spectrum from risky, potentially high-reward to low-risk, low-reward standards. It's not a good idea to invest all of your money in high-risk stocks that might collapse suddenly, nor should you invest all of it conservatively and miss out on possible opportunities. Don't put all your technical eggs in one basket.

- Buy low, sell high. Learning an emerging technology before it becomes popular can be just as hard as finding an undervalued stock, but the payoff can be just as rewarding. Learning Java when it first came out may have been risky, but it paid off handsomely for the early adopters who are now at the top of that field.

- Review and rebalance. This is a very dynamic industry. That hot technology you started investigating last month might be stone cold by now. Maybe you need to brush up on that database technology that you haven't used in a while. Or perhaps you could be better positioned for that new job opening if you tried out that other language.

The other one is the Circle of Competence. As Warren Buffet puts it: "You don't have to be an expert on every company or even many. You only have to be able to evaluate companies within your circle of competence. The size of that circle is not very important; knowing its boundaries, however, is vital." This notion is useful not because it means we should super specialize, but because it can focus us. We have a curiosity for specific topics. We have opportunities around us that are greater in some areas, peers that know a lot about certain subjects. We can leverage our Circle of Competence to learn more and learn faster.

Add more Boundary Conditions.

On a side note, this is good life advice 🤔

On a side note, this is good life advice 🤔

Every other day we see someone create a Netflix clone. Or a Spotify Clone using this or that in just one week. Some people see this and ask themselves: "Why do these companies need so many people to do something that they can build in 1 week?" Quite often, we also see people say, "What is complicated about an app that connects two persons on a map through a server?" when they refer to Uber or "Why does Amazon need almost 600.000 employees to do e-commerce?" This requires a huge answer, but I will oversimplify here: Boundary Conditions are the reason.

We don't need to know a lot about architecture to build a website that handles 1000 users doing simple reads on the same resources all day. When we have 2.8 billion monthly active users–like Facebook–or even 200 million–like Amazon–if our engineering org isn't world-class in Architecture, the service will simply not work. We don't need to write stellar and clear code when we're the only ones maintaining it. We don't need proprietary shipping and logistics innovation if we don't have Customer Obsession. We don't need an amazing Design team or know a lot about Frontend if the team tolerates bad UX. You get the idea.

Sometimes we need to push boundaries to challenge ourselves. Instead of just solving the problem, we can think about what standard we can raise and what we would need to know to raise those standards. These can be standards for what we're building but can also be for ourselves–such as always contributing to the tools the company uses or committing to always share our learnings in public. We can raise the bar in any aspect of Software Quality Timeliness of delivery, Documentation. Anything. All of these will bring us new practices, new knowledge, and new opportunities.

To find which of these standards matter the most and to understand if we're meeting them, we'll usually need to Dive Deep. We need to understand what is around the projects we want to tackle and how to audit and track our progress. Every software is part of a broader context, both technically and strategically. Diving deep into these contexts will show us a world of things we need to learn. Leverage your projects & responsibilities to become better at your craft, to dive deep, to go further. Ask for more time if you need to. Show why it matters.

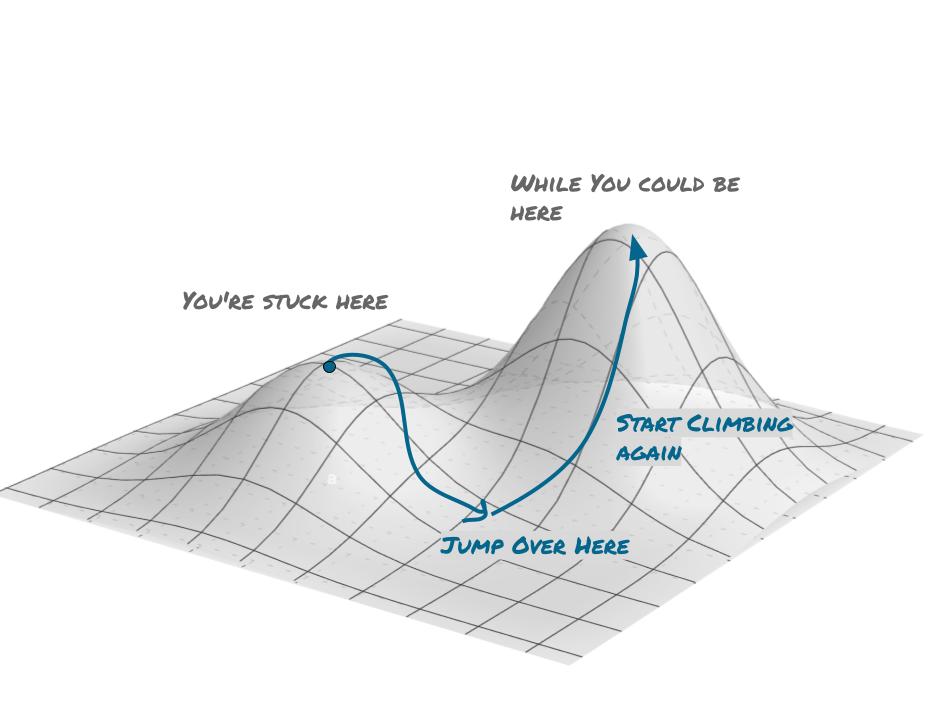

Do Random Restarts

To find Global Maxima and not get stuck in Local Maxima, in optimization, we can use a technique called Random Restarts, which are jumps from where we are to random points from which we start optimizing again. We can do that with our careers as well by taking leaps of faith with responsibilities. Starting something we're not certain we will succeed, experimenting with a new way to do things, taking on a responsibility we're not sure we can handle, taking risks.

Being smart about our restarts is crucial. Jumping too far won't necessarily lead to higher hills. But jumping too close will keep us where we are

Being smart about our restarts is crucial. Jumping too far won't necessarily lead to higher hills. But jumping too close will keep us where we are

In life, we're not randomly restarting. We carry with us our wisdom, experience, and our knowledge. Our baggage helps us reach higher hills in less time. But we need to be bold. If we always set our goals to things that we know we can do, it will be way more comfortable, we will face fewer problems, but we are also giving up on growth.

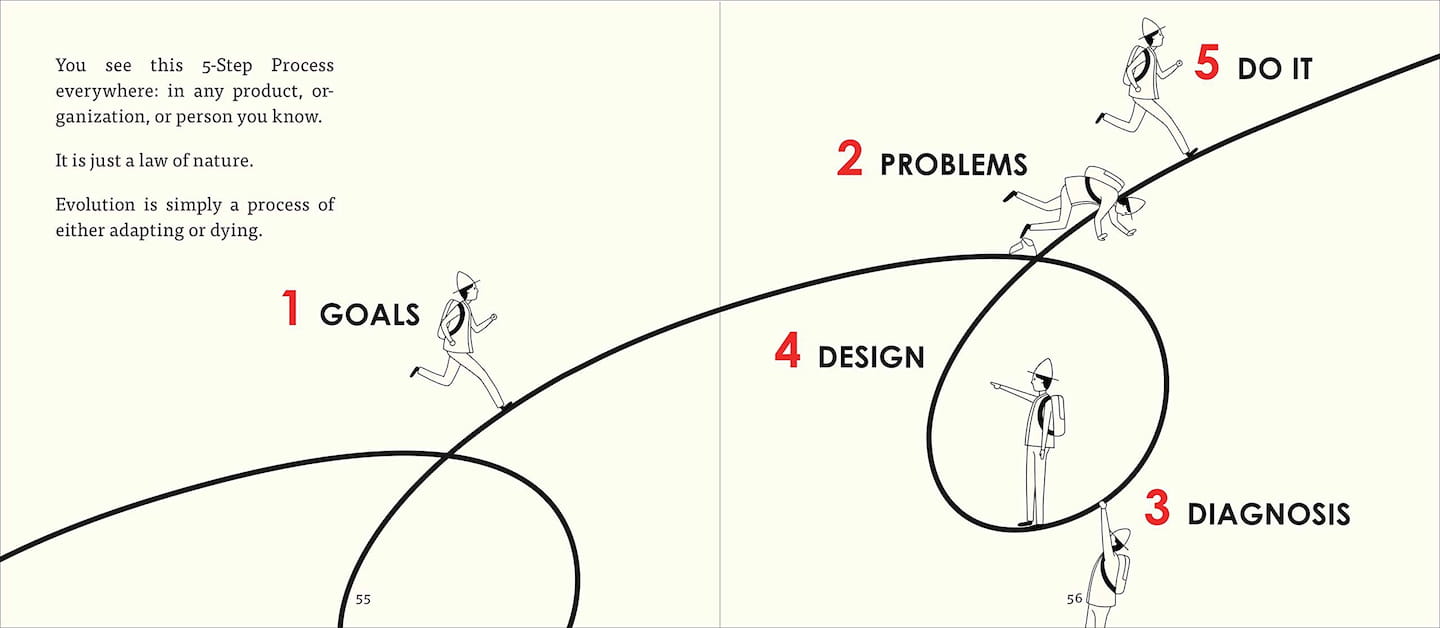

This 5 step process from Ray Dalio's Principles is a great way to think about driving for success in our careers.

This 5 step process from Ray Dalio's Principles is a great way to think about driving for success in our careers.

Finding the right moment to do this is important. And lobsters can teach us something about that: "Lobsters are soft animals living in a rigid shell. That rigid shell does not expand. So how does the lobster grow?"–says Dr. Abraham J. Twerski–" As the lobster grows, that shell becomes very confining, and the lobster feels under pressure and uncomfortable. So what it does is that it goes under a rock formation to protect itself out of predatory fish, casts off its shell, and produces a new one. Eventually, that shell becomes very uncomfortable, and the lobster repeats this process numerous times. The stimulus for the lobster to be able to grow is that it feels uncomfortable."

Sometimes in our careers, we need to molt our shells. We need to remove ourselves from our comfort zone and handle the unpleasantness that comes with it. When we're continually growing, our shells will at some point get uncomfortable. That's the moment. So keep growing. Set ambitious goals and go after them. Don't fear the pain. It signals growth.

Now I've talked a lot about responsibility, knowledge, and pushing our careers forward. A lot here is about taking risks. So I would be remiss if I did not make this important disclaimer: We are all different. We all have different tolerances for risk, we all have different ways we learn faster, we all have our limits. So one last vital thing here is listening to ourselves. Working while challenged will propel us forward faster, but burning-out can set us back months or even years. Mental and physical health comes first. Everything else comes second.